needs: Diagnosis

My beloved and I were in a small consulting suite looking at a doctor. We were wearing ‘good parents Sunday best’ dress. We were there to discuss the results of her EEG. My eyes flinched from the drab office rooms. Good news was never given in the muted tones of salmon and paired with a faded Monet poster. My sigh evaporated. She was giggly. An unexpected day off school with her parents and minus a brother put the magic in her eyes.

The appointment so far seemed straight forward. Enough so that I began to relax. It was kind of fun to watch our bubbly girl charm the doctor. He measured, weighed and chattered to her. She confirmed she was 5, had a brother, liked to dance and eat cannoli. She skipped out to the waiting room and took all the joy with her as well as his super enthusiastic voice. The door closed, he said “There is a subtlety to her kind of epilepsy that can be challenging.” I stopped breathing. I didn’t see that coming.

In movies there is always a serious announcement, followed by a genuine empathetic look from the doctor and a pause. There is a second where people pick their hearts and brains off the floor. For us, this dead weight revelation was dropped incidentally. My mind scrambled as he waved a glossy chart of 40 different pills around. After he said the word epilepsy, everything he said hung in the air between his lips and my brain. I glanced around those words to the door. I wanted to hold her, outside of that room. Beyond the door was a world where she didn’t have epilepsy, yet. I wanted desperately to be on the other side of that door.

“Can you stop for a minute?” my beloved said. And the air in the room shifted. My beloved had stopped the autopilot download of information from the wise and well-travelled breaker of parents’ hearts. My beloved firmly asked him to stop again and I looked back from the door to my beloved. He was twinkling in the sunlight from the window for a second, was washed in a golden armour. In the toddler years, my beloved didn’t leave me breathless often, but there it was. I believed he was going to ‘return to sender’ the epilepsy. That was where my mind went. Instead, he took it like an unwanted jacket and put it on. “This is the first time anyone has said …. epilepsy to us, and we need a minute, we will have questions and we need some basic information.” It felt like a betrayal. I drew another breath and switched. I loved him hard for that shift. It was the first time he had changed the tempo and the rhythm of a medical appointment. Now he plays it like a party trick. We all do.

The meeting slowed and the doctor started to print things off his computer and hand them to us. There was a sheet on epilepsy and support groups. There was a sheet on medication. There was a sheet on the tests she had to have. There were lots of sheets and I shoved them into my handbag. When the doctor was done he stood and moved to the door. Without the answers to the questions we couldn’t voice, we followed and left the room. We paid the money we didn’t have, for the information we didn’t want, and rebooked for the appointment we were already dreading. The three of us floated to the car on a cloud fuelled by her chatter. That drive was the first time we spoke silently in small hand touches over the gear stick while she sing sang to us from the back seat.

As a working family, the day was pre-planned. My clients were seeping into me via emails, and his work was tapping him with the pulsing light on his phone. I was dropping him at the office, and her at childcare, before going to work. The plan was to slip back into our life, as if nothing had changed. I followed the plan. It seemed a good enough place to hide.

Later, my phone was persistent, and it was irritating. I was busy and had something to sort out. I was not in the mood for multi-tasking. I looked up searching. Scanning for what I wanted. Everything seemed out of reach and harder. My phone was demanding. I reluctantly answered unleashing an impatient “Yes”-*sigh* combination on the caller.

“Where are you?” my beloved asked quietly and calmly.

“I’m just taking care of something.” I said, trying to sound vague.

“I shouldn’t have come to work. I should have stayed with you.” His confession didn’t sound like the captain of industry that usually called me.

“Oh, its ok. I’m fine.” I had a Stepford, ever so controlled response. I wasn’t in the mood for compassion.

“Where are you?” He wasn’t going to be fooled. Fucking background noise.

“I’m just buying a Barbie campervan.” I confirmed matter of factly.

“Yes, I’ve heard that cures epilepsy” he said and laughed quietly as a single tear crawled down my face. I laughed too.

“I’m coming home” he said.

“I’ll see you there” I rushed toward the register (with my campervan).

We were all going to be together. This called for Doona Island.

means: Shit we do when we have tough news in a medical appointment

- Toilet and Parking. I always allow for extra parking time and toilet time before an appointment. I can’t hear anything if I am going to piss myself or I’m worried about the parking. Once I go through the door, the timeframe is not mine.

- Have a folder. I have a nifty folder to put any print outs so they don’t end up in the bog of eternal stench or trash compacter that is my handbag. I love Kmart for this and, well, everything.

- Take the roll. I get to choose who is in the room in a meeting and I can stop at any time and ask for my kids to be in the waiting room. iPads, Audio books, books and drawing are secret weapons at this time. If it’s not a waiting room I want them in, I have headphones and a movie at the ready.

- Write it down. I have paper and pen and I’m not afraid to use it. The action of writing helps processing and makes the speaker accountable. I use it to slow things down and record the questions I can’t ask in that moment.

- White down search terms. Make a note of any key google terms or websites.

- Slow it down. When a meeting isn’t going the direction or pace I want it, I slow it down, interrupt or interject and clarify something. It buys me time. Doctors are frequent flyers with this, but this was my first rodeo.

- Arrange a follow up call or email. I always have questions, so I make a time before I leave that room to have a follow up call or email. I am always more likely to get a response, if they know the questions are coming.

- Be gentle. Commitments can wait. Have a kindness plan to look after each other. I just block out the rest of the day or night leaving space for some family down time.

- Start a “things to ask” list. I put my questions somewhere so they don’t keep swirling around my head. I find the answers to most of them myself. Anything I can’t work out, I take back to my GP. She is more available than a specialist, and she bulk bills. (my link why you need a good GP)

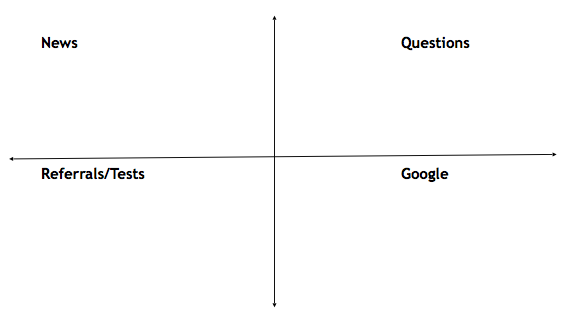

tools: notebook grid for appointments